Remembering Stella Chiweshe, Queen of Mbira

Stella Rambisai Nekati Chiweshe

8 July 1946 - 20 January 2023

Kristyan Robinson remembers Stella Chiweshe:

‘Mbuya Stella has ascended.’ The unexpected news came with a gasp in a What’s App message from my eldest son in Zimbabwe just before noon on 20 January 2023.

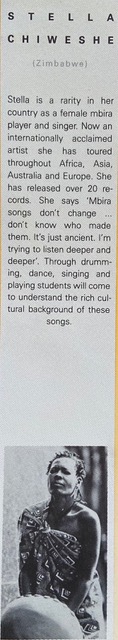

Mbuya, Shona for grandmother, is also used to respectfully address young women and girls who show the revered qualities of wisdom and patience, as well as a preference for Shona culture over the distractions of modern life. As a young girl growing up in Mhondoro Stella Rambisai Nekati Chiweshe yearned to play mbira, the traditional instrument of Zimbabwe played in ceremonies to summon and praise ancestral spirits. Mbira was the preserve of boys and men and Stella’s interest in playing was discouraged until her uncle noted her persistence and began to teach her. She never looked back and was unflinching in her dedication to mbira and to her Shona culture.

Mbira music and most other significant aspects of Shona culture were strictly banned by the British coloniser. To play mbira was an act of subversion. Stella was the great-granddaughter of VaMunaka, the medium of the great spirit Kaguvi. VaMunaka was a spiritual leader during the Second Chimurenga and the spirit Kaguvi guided the freedom fighters in the war against the British until VaMunaka was captured, hung and decapitated by the colonisers. Stella had the fight for liberation in her blood. Her song ‘Chachimurenga’ was a battle cry to rise up, to fight for freedom. It was, she told me, not just a call for political freedom from the ruling oppressor, but for personal freedom, for human rights in the face of any oppressor.

Stella was Chihera - from the Eland lineage or totem. The Eland is a solitary, independent antelope known for its remarkable endurance. Stella toured and recorded internationally with her Earthquake Band, fusing mbira and marimba with guitars. But later in life she performed alone, always to honour her ancestors. She said, “If I am with mbira, I am not alone.’ Alone - with her mbira - she could hold an audience with her virtuosity, improvising and sailing along on her instrument, customised with additional keys, singing in a rich medley of tones and vocal techniques. She played hosho and drums and danced with the same virtuosity and was entrancing on stage.

Stella was Chihera - from the Eland lineage or totem. The Eland is a solitary, independent antelope known for its remarkable endurance. Stella toured and recorded internationally with her Earthquake Band, fusing mbira and marimba with guitars. But later in life she performed alone, always to honour her ancestors. She said, “If I am with mbira, I am not alone.’ Alone - with her mbira - she could hold an audience with her virtuosity, improvising and sailing along on her instrument, customised with additional keys, singing in a rich medley of tones and vocal techniques. She played hosho and drums and danced with the same virtuosity and was entrancing on stage.

In 1989 Stella was one of twelve international women artists invited to perform and lead workshops at The Magdalena International Festival of Voice. It was an extraordinary event. The artists were all outstanding and it was difficult to choose who to work with. I chose to work with Stella, because her programme description mentioned that, as well as singing, we would be dancing and I wanted to move. For ten days Stella played mbira for us. She asked us to sit and to listen deeply. I had never heard mbira. Its complex rhythms and layered sounds transported me in time. Stella taught us to sing Shona songs and to dance mbira style. She had toured internationally with the National Dance Company of Zimbabwe early in her career. At the end of the Festival Stella invited me to Zimbabwe.

I took her up on her offer. The night I arrived we drive to her mother’s village. By morning word is out that Stella has arrived. Mbira players walk from far and wide to play for and with Mbuya Stella. Reed mats are spread outside in the shade and they sit and play. Stella’s late brother Elfigio, also a gwenyambira (mbira player) plays too. Stella patiently teaches her nephew Lloyd and even more patiently teaches me. On the drive back to Harare we pass a long queue of women with maize meal sacks on their heads, waiting outside an electric mill. Stella slows the car and asks me to listen. I say all I can hear is the loud screeching sound of the machine grinding the maize. She tells me that the machine is saving women time but at a cost: the songs, she says, are being lost. She tells me that when the maize is pounded by hand, two or three woman with babies tied to their backs working around one mortar, raising large wooden pestles and pounding in turn - fwump…fwamp… fwump - making a rhythm, they sing songs that their grandmothers sang, singing to each other, to their children and to the maize. Stella tells me that the song the women sing permeates the food. She is unsettled by the conflict - this modern development helping in one way but robbing something precious. She is committed to preserving these songs and others associated with women’s roles in traditional rural life.

I saw her last in London, at the Jazz Cafe in July 2019, before the pandemic. The place was rammed and most of the crowd were Zimbabweans. Stella spoke only Shona between songs and the crowd loved it - even those of us who didn’t understand her jokes or deep Shona reasoning. At the end of the gig she floated off stage and settled to the side in a dim pool of light. Many of us gathered and knelt in a circle surrounding her. She was regal and held court with good humour and delight. After that she spoke to me about the Chivanhu Foundation she was building on her father’s land - a centre dedicated to Shona heritage and culture. On her website she writes, “I absolutely want to leave something to my country, to my people. Returning to my father's land to create this music centre is a real dream for me. I want to revive links between music and the ancestral culture of Zimbabwe. Practising these traditions can build a more stable future.”

The huge impact Stella Chiweshe has had on my life is clear. I never stopped playing mbira. I lived for years with the late Chartwell Dutiro with whom Stella had played in clandestine bira ceremonies prior to Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980. Our eldest son, Shorai, has returned to live in Zimbabwe. Our youngest son, Kudakwashe, lives in London. We all still meet with friends and family whenever we can to play mbira. When we heard that she had passed, Kudakwashe said, ‘Mbuya is a big reason for our existence and a big part of our history’ so we gathered and played for her spirit, as did all the mbira players around the world and especially in Zimbabwe on hearing the sad news.

The huge impact Stella Chiweshe has had on my life is clear. I never stopped playing mbira. I lived for years with the late Chartwell Dutiro with whom Stella had played in clandestine bira ceremonies prior to Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980. Our eldest son, Shorai, has returned to live in Zimbabwe. Our youngest son, Kudakwashe, lives in London. We all still meet with friends and family whenever we can to play mbira. When we heard that she had passed, Kudakwashe said, ‘Mbuya is a big reason for our existence and a big part of our history’ so we gathered and played for her spirit, as did all the mbira players around the world and especially in Zimbabwe on hearing the sad news.

Stella divided her time between her home in Berlin and her kumusha in Zimbabwe. She knew she was ill with cancer and returned to Zimbabwe, finally, to her native soil. She was granted a state assisted funeral with a traditional burial exactly according to her wishes.

Stella is survived by two daughters, Charity and Virginia Mukwesha.

Kristyan Robinson